“The People all new Settlers, extremely poor—Live in Log Cabins like Hoggs,” wrote Charles Woodsmason, author, poet, and Anglican clergyman, in 1766 while visiting South Carolina. In 1865 it was written that, “hardly a poor woman’s cow on [Cape Cod was] not better housed and more carefully provided for than a majority of the white people in Georgia.”

“The People all new Settlers, extremely poor—Live in Log Cabins like Hoggs,” wrote Charles Woodsmason, author, poet, and Anglican clergyman, in 1766 while visiting South Carolina. In 1865 it was written that, “hardly a poor woman’s cow on [Cape Cod was] not better housed and more carefully provided for than a majority of the white people in Georgia.”

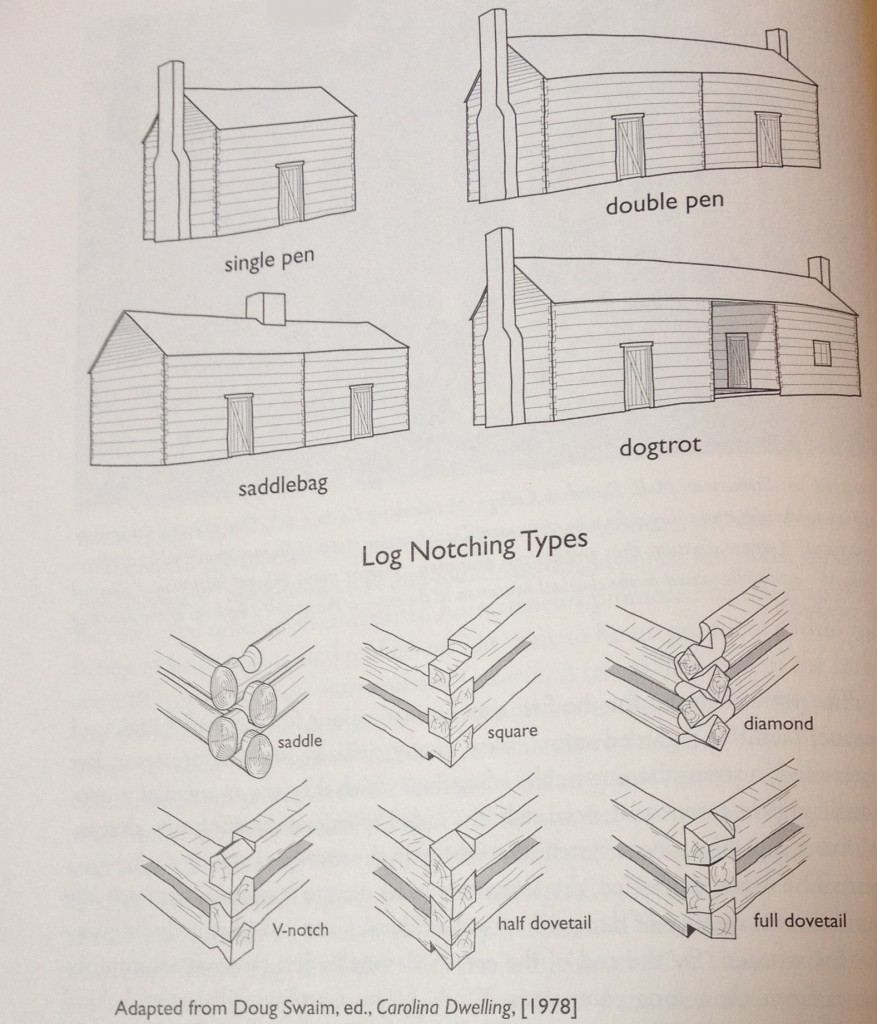

What is interpreted as simple architecture more suitable for livestock represents the outcome where form is dictated by function. Log cabins, which dominate much of the Southern landscape, reflect this focus on function. Not surprisingly, in 1939 a survey of the Southern Appalachians found that 11.4% of the homes were log cabins compared to the national average of 3.7% (by county). The reason for this other than affordability, is that log cabins because of their thick, dense walls remain cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter than a traditional frame house.

Traditionally log homes have been smaller, not a reflection of the economic state of the owner, but rather the size of nearby trees. A log house is limited by length of the logs, and regional sizes reflect the sizes of trees. While techniques to create longer walls and room extensions exist, they were often complicated and rarely used.