The greatest joy of the South is undoubtedly a fresh biscuit with Tupelo honey. That is until you realize that the honey is a product of multiple regurgitations.

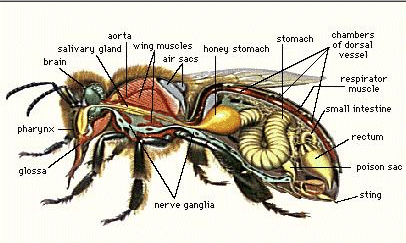

We tend to focus on the beautiful part of the process where a honey bee visits a flower for the nectar. It seems we bee-leave (ha) that they carry little bee-sized buckets for nectar transport. I guess in a sense they do in that the bee-sized buckets are their bee-sized organs. Actually it is a honey stomach, a bulbous area, technically a crop, right before the stomach that stores liquids for later regurgitations. At the hive, the worker bee will regurgitate and ingest the nectar multiple times. The worker bees will do this a group until the vomit mixture is just the right mix.

We tend to focus on the beautiful part of the process where a honey bee visits a flower for the nectar. It seems we bee-leave (ha) that they carry little bee-sized buckets for nectar transport. I guess in a sense they do in that the bee-sized buckets are their bee-sized organs. Actually it is a honey stomach, a bulbous area, technically a crop, right before the stomach that stores liquids for later regurgitations. At the hive, the worker bee will regurgitate and ingest the nectar multiple times. The worker bees will do this a group until the vomit mixture is just the right mix.

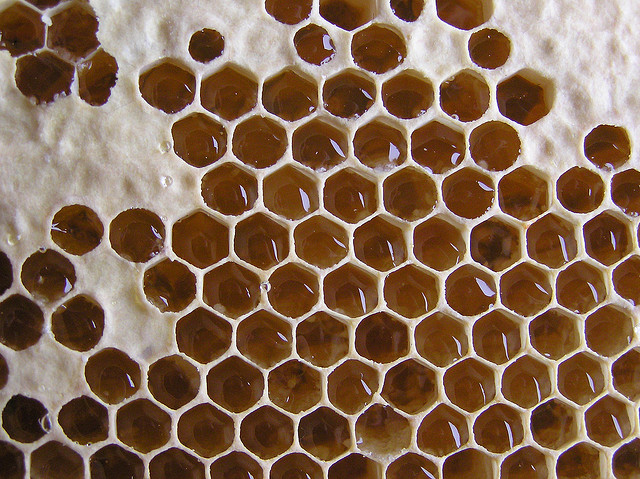

During this time an enzyme, invertase, and digestive acids turn the surcrose, by hydrolyzation, into the simple sugars of glucose and fructose. Another enzyme, glucose oxidase which as the name suggests oxidizes glucose produces hydrogen peroxide and gluconic acid. The acid considerably lowers the pH (~3-4) of the honey. After the cycle of puking and eating, evaporation takes over in the unsealed honey comb to achieve the final viscosity of honey. Bees inside the hive will actually fan their wings to create a draft to aid in the evaporation. Because of this lack of water, acidity, and presence of hydrogen peroxide, few bacteria or microbes can actually live in honey. In fact honey is so dehydrated it is hygroscopic, i.e. attracts water, and thus any living thing will have the water pulled from by the honey.

But as I sit here and consume my honey-filled biscuit, I don’t care about any of this nectar vomiting business.

Feature photo by Johan J.Ingles-Le Nobel on Flickr via CC