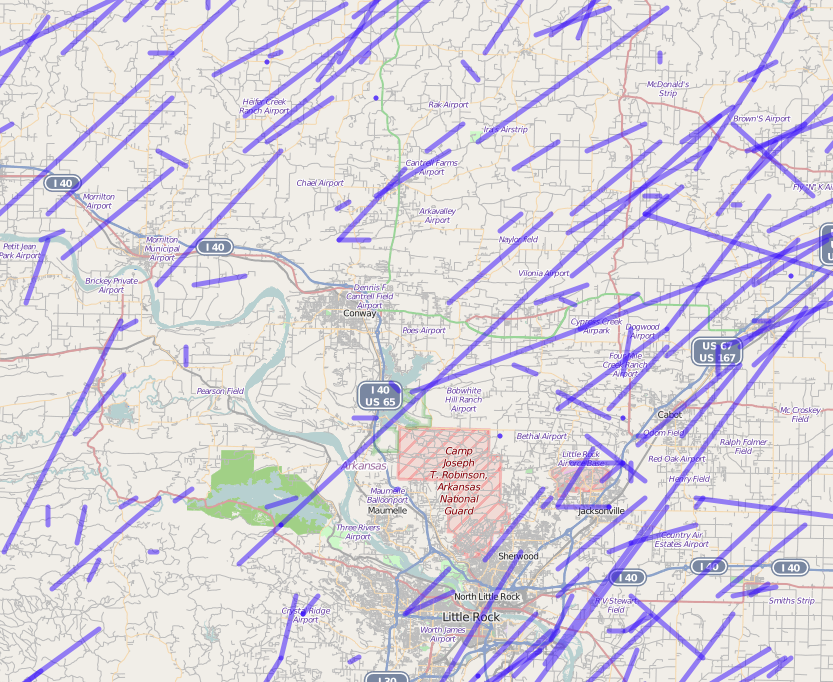

Conway rests almost square in the middle of Arkansas. In the early 90’s when I attended college in this Southern town there were fewer than 30,000 people. Outside of the Old South Pancake House, a Wal-Mart, and the annual Toad Suck Daze, nothing much occurred, not even tornadoes, a rarity in a town also squarely in Tornado Alley. Just a few minutes away sets Vilonia, a town of a few thousand that makes Conway look like a sprawling metropolis. What Vilonia lacks in cultural exhilaration is more than made up for in meteorological excitement. In 2011 an EF2 tornado wiped out a small part of the town. In 2014 and EF4 wiped out the rest. But Vilonia has nothing on Moore, Oklahoma. In 1998, 1999, 2003, 2010, twice in 2013, and again 2015, tornados have struck this town just south of Oklahoma City. Since the town’s founding in the late 1800’s over 20 tornados have removed parts of this small town.

Conway rests almost square in the middle of Arkansas. In the early 90’s when I attended college in this Southern town there were fewer than 30,000 people. Outside of the Old South Pancake House, a Wal-Mart, and the annual Toad Suck Daze, nothing much occurred, not even tornadoes, a rarity in a town also squarely in Tornado Alley. Just a few minutes away sets Vilonia, a town of a few thousand that makes Conway look like a sprawling metropolis. What Vilonia lacks in cultural exhilaration is more than made up for in meteorological excitement. In 2011 an EF2 tornado wiped out a small part of the town. In 2014 and EF4 wiped out the rest. But Vilonia has nothing on Moore, Oklahoma. In 1998, 1999, 2003, 2010, twice in 2013, and again 2015, tornados have struck this town just south of Oklahoma City. Since the town’s founding in the late 1800’s over 20 tornados have removed parts of this small town.

All this begs the question, are some areas more tornado prone?

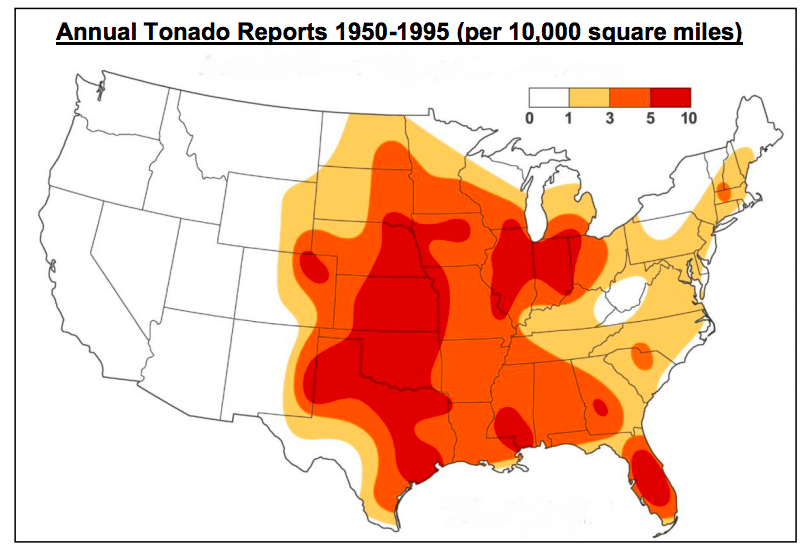

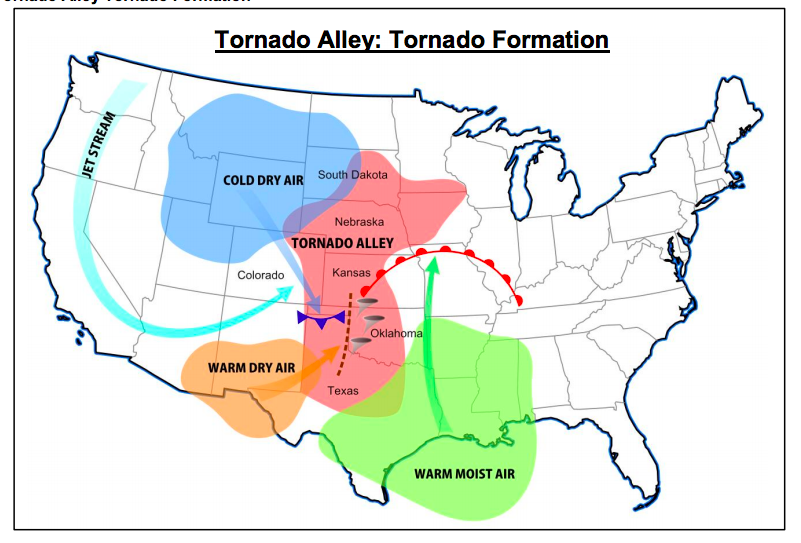

Over very broad scales this is most certainly true. The area known as Tornado Alley sees the clash between warm moist air from the Gulf of Mexico near the ground, colder air in the upper atmosphere from the west, and a third layer of very warm dry air between the two levels from the southwest that tries to keep the other two at bay (see background at this post).

Over very broad scales this is most certainly true. The area known as Tornado Alley sees the clash between warm moist air from the Gulf of Mexico near the ground, colder air in the upper atmosphere from the west, and a third layer of very warm dry air between the two levels from the southwest that tries to keep the other two at bay (see background at this post).

Although it covers just 15% of the U.S., Tornado Alley lays claim to nearly 30% of all the confirmed tornadoes in the Storm Prediction Center’s database between 1950 and 2012. Of the 58,046 tornadoes on record in that period, 16,674 of those occurred in Tornado Alley, which is a long-term average of 268 tornadoes per year.-ustornadoes.com

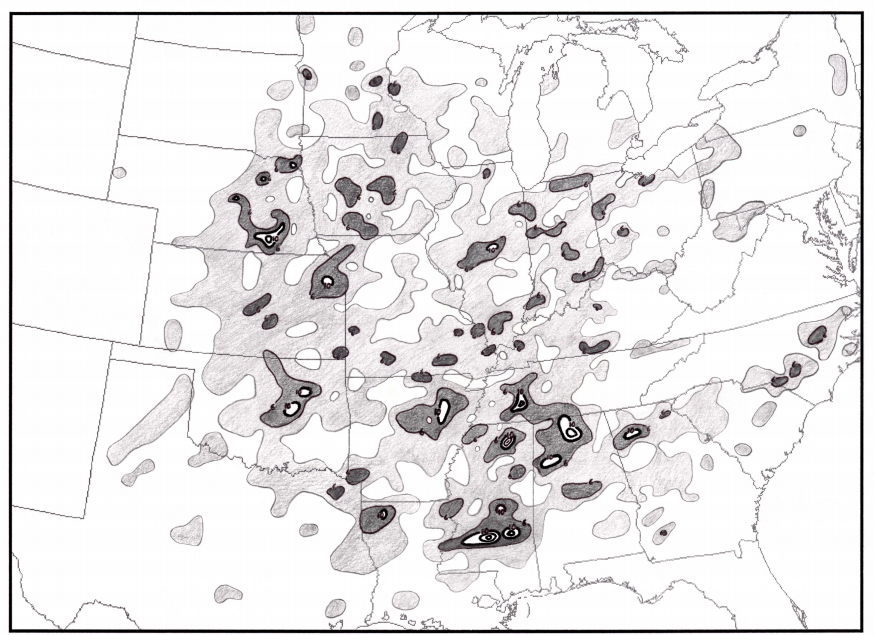

But at more local scales are some areas “protected” or “off limits”? Over a decade ago, meteorological researchers Chris Broyles and Casey Crosbie at the Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Oklahoma proposed that are “smaller tornado alleys.”

But at more local scales are some areas “protected” or “off limits”? Over a decade ago, meteorological researchers Chris Broyles and Casey Crosbie at the Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Oklahoma proposed that are “smaller tornado alleys.”

Many smaller tornado alleys were identified across the Mississippi Valley, Tennessee Valley, Great Plains, Ohio Valley and Carolinas. Though there may undoubtedly be specific meteorological reasons why these apparent alleys exist, one hypothesis is the smaller alleys are related to topographic features that may modulate environmental conditions in ways that favor development of these types of tornadoes.

One adage is that “tornadoes don’t happen in the mountains”. As someone who grew up in the Ozark Mountains and saw my high school demolished it’s not a belief I personally hold but anecdote does not make science. It does appear that tornados are less frequent in the mountainous areas due increasingly colder temperatures with increased elevation. This cold denser air at higher elevations is more stable—not exactly the best trigger for a tornado. Yet, while tornados are less frequent they do still occur in the mountains. Just as one example, an EF3 tornado hit at 2,080 feet over Glade Spring, Virginia in April 2011.

Researchers at the University of Alabama at Huntsville have also found the roughness of that topography can also influence the power of tornado. Kevin Knupp lead of the research team states, “Forested areas have a rougher surface than open agricultural regions. Forested regions over mountains are even rougher because the mountain topography has a certain roughness associated with it.” In simulations, the rougher the area the stronger and wider a tornado can get in simulations. Another researcher in this group, Anthony Lyza, has started providing evidence that tornadoes in Alabama are affected by topography. Tornadoes weaken as they proceed up and strengthen as they proceed down mountains and hills. Sometimes whether uphill or downhill a hill or mountain will just cause a tornado to dissipate. Circulation will intensify as a tornado moves onto and weaken as it moves off a plateau. Tornado tracks will deviate to follow plateau edges and valleys.

In the map above (from Broyles and Crosbie) you note a mini-tornado alley in the Northeast Arkansas. Changes in topography from the forested mountains of the Ozarks to the flat farmland of the deltas of the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers lend some credence to Knupp’s hypothesis. In combination with this topographic change, Gulf of Mexico moisture running up the Mississippi river may also bank against the mountains leading to minor atmospheric instabilities that trigger tornadoes.

In the map above (from Broyles and Crosbie) you note a mini-tornado alley in the Northeast Arkansas. Changes in topography from the forested mountains of the Ozarks to the flat farmland of the deltas of the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers lend some credence to Knupp’s hypothesis. In combination with this topographic change, Gulf of Mexico moisture running up the Mississippi river may also bank against the mountains leading to minor atmospheric instabilities that trigger tornadoes.

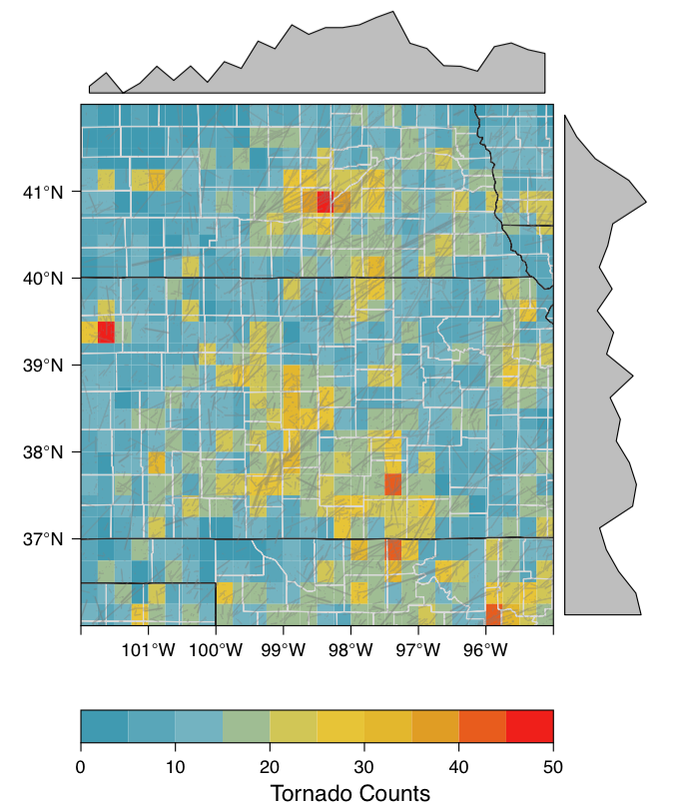

Yet variance in the number tornadoes from location to location may be just biases in reporting and spotting tornadoes in unpopulated regions. James Elsner and team at Florida State University found that “historically, the number of reported tornadoes across the premiere storm chase region of the central plains is lowest in the countryside,” a pattern greatly mitigated in recent years due to storm chasers.

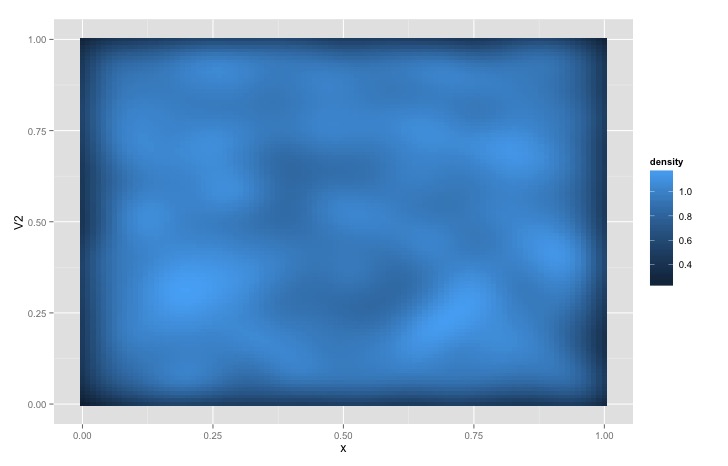

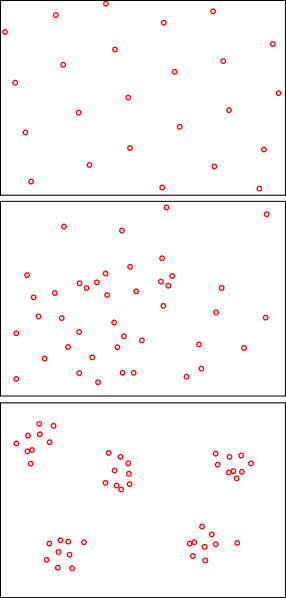

There may be another reason for mini-tornado alleys. Randomness. Humans are almost completely useless in detecting spatial patterns. To clarify, we specifically have difficulty separating random from clumped patterns, especially when the clumpiness of events is weak to moderate. Keep in mind that small amount of clumping happens in truly random processes. Take the figure below. I generated 1,000 random numbers between 0 and 1. I generated another set of 1,000 random numbers between 0 and 1. I used these to represent the x,y coordinates of simulated tornado touchdowns on my hypothetical tornado alley. You can clearly see that simulated tornadoes are clumped in some regions. Compare this to a figure James Elsner posted on Twitter (far bottom) of actual tornado frequencies in Kansas.The next step for tornado research is to separate random pattern from actual areas that see more than their fair share of tornadoes.