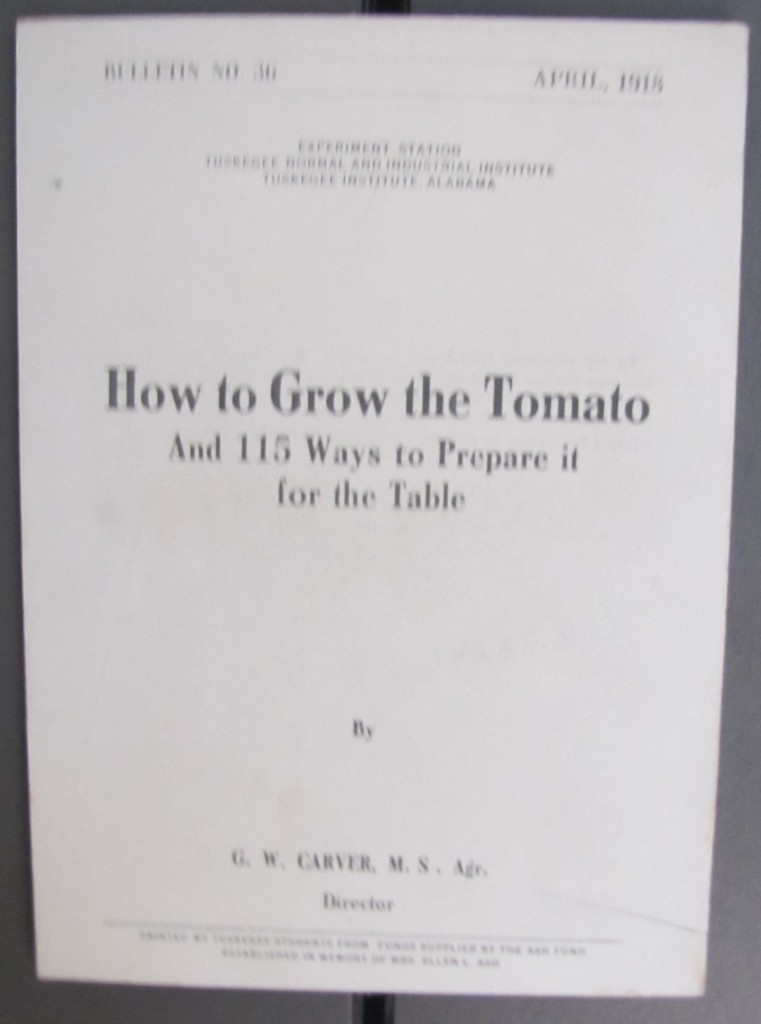

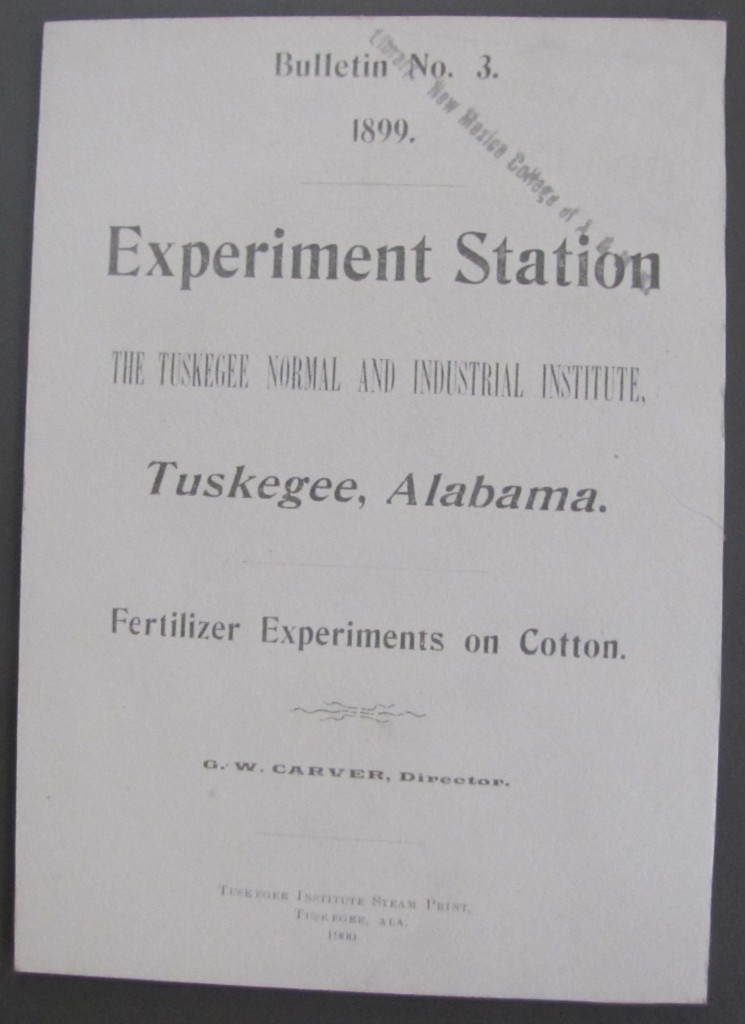

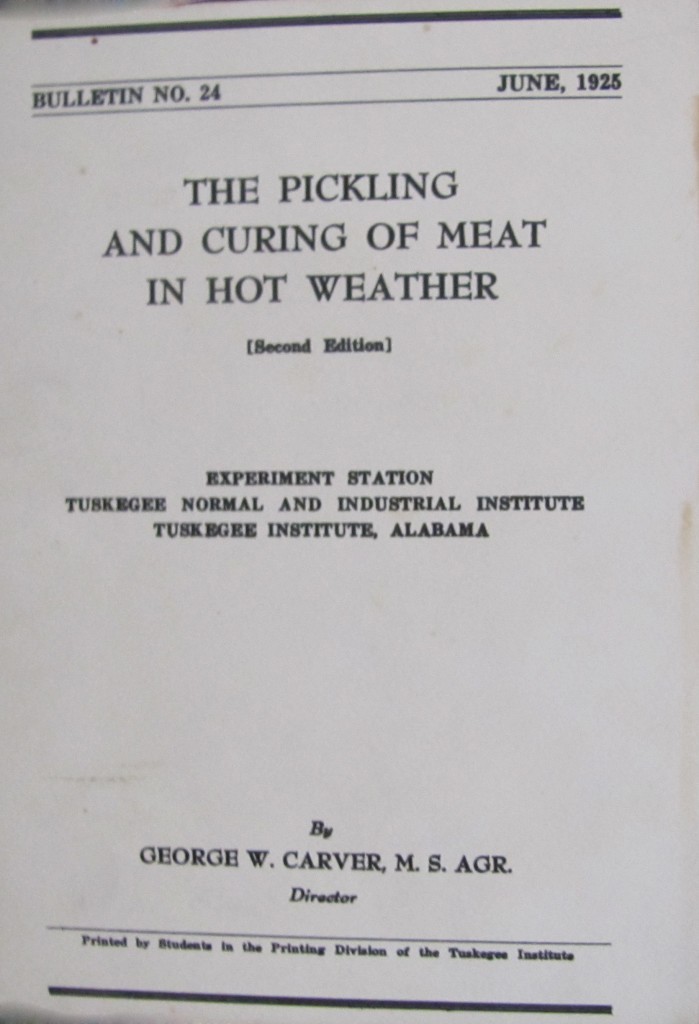

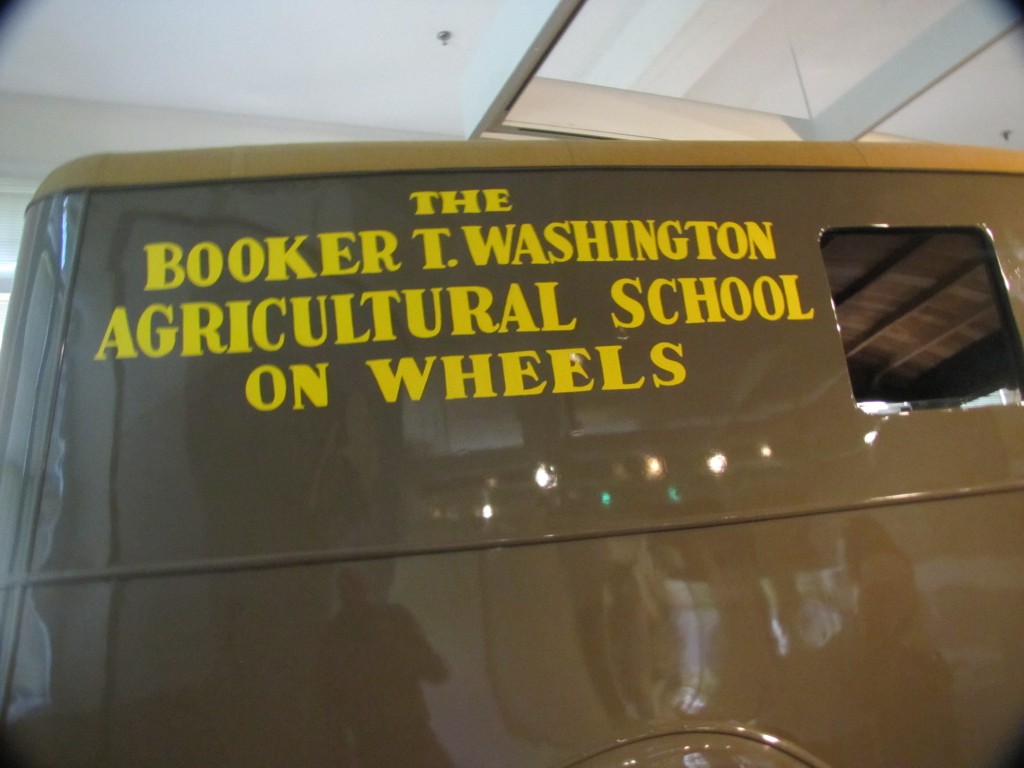

In 1896, Booker T. Washington, the university’s president, invited George Washington Carver to head its Agricultural Department. He spent 47 years at Tuskegee developing numerous inventions and agricultural practices. He was likely one of the first scientists to initiate extension programs and actively train farmers. The same farmers would often be recruited into Carver’s research in an early form of citizen science.

I have always found Carver a compelling figure. Born into slavery, Carver rose to become one of the most important and influential scientists of his time. Carver was a true renaissance man; he taught piano at the University and loved to crochet. Carver also represents yet another dichotomy of science in the South. In the early 1900’s when Carver began his career, very few university educated African-Americans existed. To this date, the representation of African American in science is appalling low. However, Carver revolutionized agriculture from cotton to peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes, crops now inseparable from Southern culture. No scientist has had such a profound influence on the South.

Equally intriguing is that Carver’s dedication to science was only matched by his dedication to Christianity. Carver carried a bible every day and taught a bible class on campus. He developed walnut dies and stained the pews from a local church. Carver’s evangelism led to disapproval by many in the scientific establishment. In contrast, the local Alabama and university loved him.

In August, I had the privilege of visiting Tuskegee University. Dana Chandler, chief archivist for Tuskegee University, showed me items belonging to Carver. I am indebted to Dana, himself a man of science and religion and scholar of Carver, for discussing Carver’s life and legacy with me.