Jeff Beane was on a mission. In 1992 and 1993, he spent 1,500 hours traveling across North Carolina. In that time he traversed over 10,000 miles across the state. Jeff navigated rivers, swamps, oxbow lakes and numerous other places by day and night, often by canoe or johnboat but just as frequently by wading. Despite rain, shine, mud, and stench he patiently looked and listened. He visited places in conditions most wouldn’t. Jeff has been doing this since 1987 and not once has he found what he was look for—the river frog, Rana heckscheri.

At one time the river frog ranged from the coastal plains of northern Florida into southern North Carolina favoring “blackwater” creeks and cypress swamps. The blackness of these waterways arises from the decaying of leaves and plants in the slow moving waters. As the vegetation decays, tannins leach into the water staining the color of sweet tea to black coffee, the perfect brew for the river frog.

The river frog has never been abundant or widespread in North Carolina, only a handful of individuals have been recorded and only from five sites. In only one of the sites on the Lumber River, between the towns of Wagram and Maxton, was the river frog seen more than once. Although for nearly a decade in the 60’s and 70’s tadpoles were seen at the site suggesting adults were…ahem… breeding. In 1975, almost 40 years ago, the last river frog seen in North Carolina was collected in this same river spot. Thus began Beane’s quest to rediscover Rana heckscheri in North Carolina.

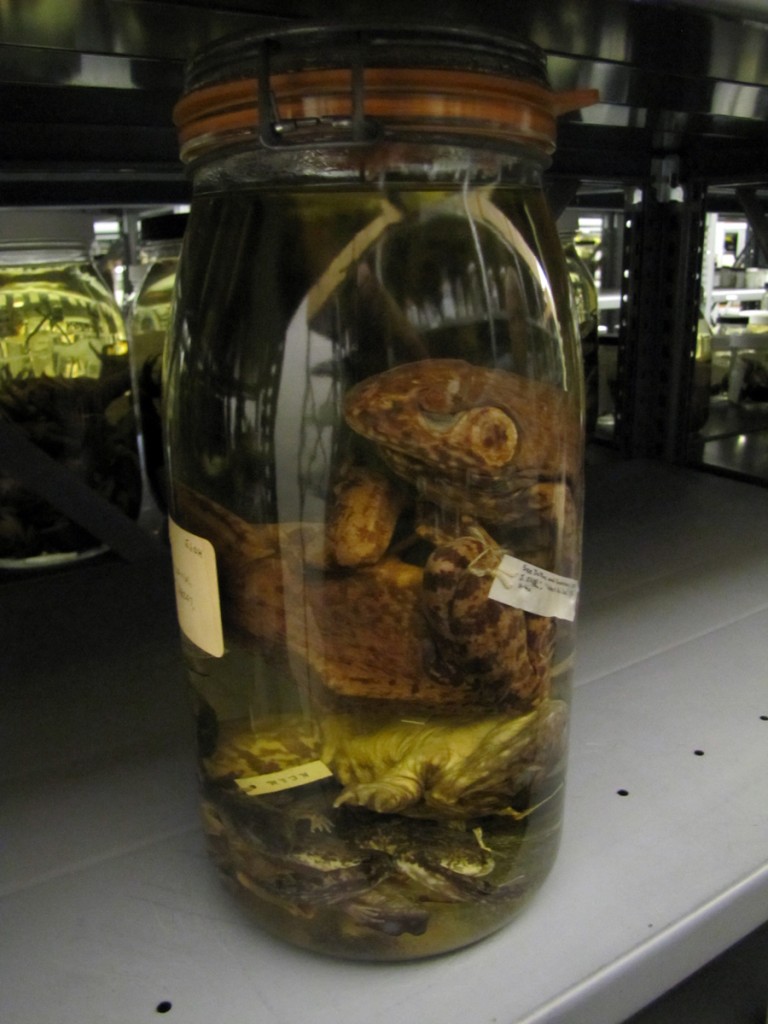

Beane’s, or anyone else’s, inability to find it the state may merely reflect it never really occurred in North Carolina with any real gusto. It may occur in North Carolina, albeit in small numbers, but is simply overlooked. This is the proverbial needle in a haystack. That might be the case if the river frog didn’t possess a whole variety of features and behaviors that make it the practically impossible to miss. Take the size for instance. The river frog at half a foot long is the second largest in North Carolina, only outsized by the American bullfrog. The tadpoles are larger than your thumb, reaching 4 inches in length, and rank among the world’s largest. The tadpoles also school and move in a massive swarm. They are not exactly elusive. And then there is the distinctive call (listen here), a cross between a chainsaw and semitruck downshifting to a low gear.

But…Beane and nobody he interviewed have seen the species in North Carolina in four decades.

Why the absence? That is the real mystery. Amphibian declines are occurring globally due to habitat loss, climate change, and pollution. North Carolina may never have been prime habitat for Rana heckscheri —perhaps too the state is too cold during the winter or there is a lack of the preferred breeding of oxbow lakes. The small numbers made it prone for a local extinction. Beane details, ironically in a North Carolina science journal now also extinct, three possible scenarios. Frog gigging, a sort of spearing of frogs, is still a popular pastime. The large size Rana heckscheri make it a prime target for its large meaty legs good for frying. The river frog also doesn’t flee when approached. Instead they play dead and while limp secrete a horrible smelling fluid, a strong but imperfect deterrent. The American bullfrog with its large size and general robustness may also be a superior competitor driving river frogs out region they already fair poorly. Last, a general decline in water quality in the state. Ultimately, we may never know what happen to the river frog in North Carolina. In Beane’s own beautiful words

“But I still haven’t written off Beane details three possible. For any who care about such things as extinction, the ivory-billed wood-pecker recently personified Emily Dickinson’s dictum “Hope is the thing with feathers.” But hope can also be the slimy, toxic-skinned thing with a voice between a belch and chain saw. These days I focus on studying animals that I can actually find. But now and again I still visit those burrow pits along the Lumber where the big, olive brown fogs and their big, striped tadpoles, once lived, and I stare at the dark water, and it looks dead and empty to me. And always, when around blackwater river bottoms, I look and I listen, hoping still to rediscover a creature that nobody knows or cares is missing. Well, almost nobody.”

Beane, J.C. (1998) Status of the river frog, Rana heckscheri (Anura: Ranidae) in North Carolina. Brimleyana: The Journal of the North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences. 25:69-79

Beane, J.C. (2005) The frog nobody missed. Wildlife in North Carolina 69:20-25