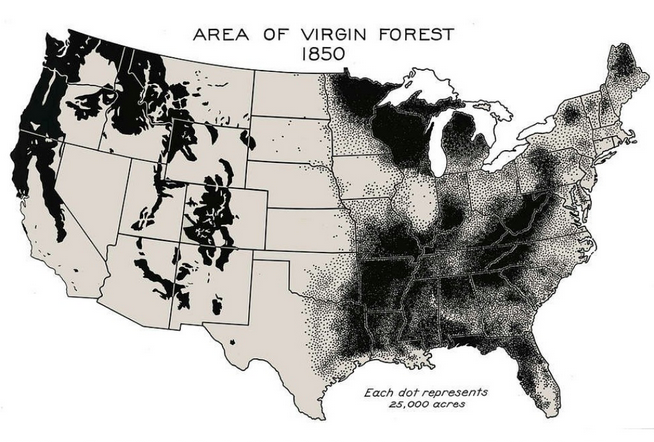

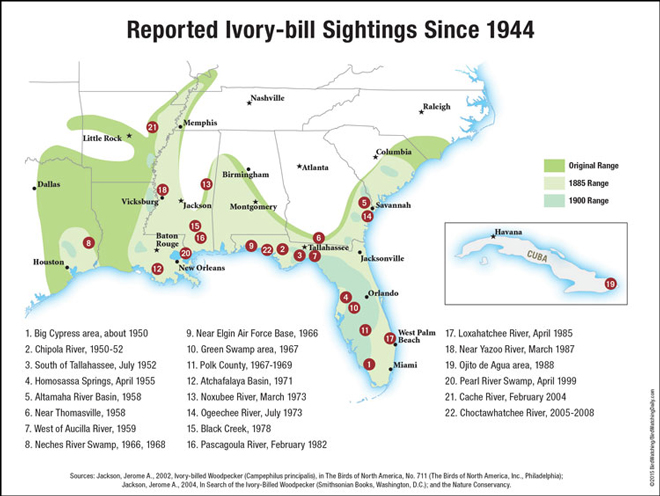

A century ago a swampy forest, The Big Woods, stretched from Memphis to Little Rock, nearly 24 million acres worth. This was the treasured territory of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, the striking over-sized bird that fed off insects in the masses of dead and decaying trees in these wetland forests. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker is not only unique because it is one of the largest woodpeckers and it sports a distinctive red crest, but it has also become a deep fascination in Southern Lore, a bird so beautiful that it caused people to exclaim “Lord God! What a bird!” upon seeing it, a statement that gave rise to the Ivory-bill’s other name, the Lord God Bird.

But the symbol of the Ivory-bill no longer means what it once did. “This has been the symbol of what we did wrong. The complete annihilation of one of America’s most treasured and spectacular pieces of land. We cut it all,” stated John Fitzpatrick, head of the Lab of Ornithology at Cornell University.

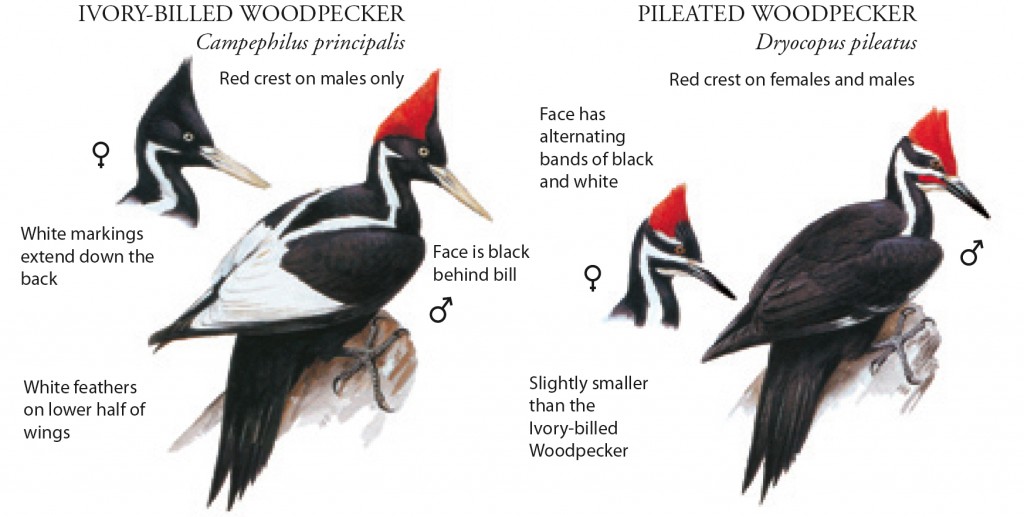

During the Reconstruction Period after the Civil War, vast swaths of the Southern Forests were mowed down. Today all that remains of The Big Woods is a small 500,000-acre sliver. And with this loss Ivory-Billed Woodpecker populations rapidly declined. Despite warnings a decade earlier, many Southerners fought the news. In 1932 a Louisiana state representative, Mason Spencer, disproving of the reports heralding the demise of the species killed an ivory-billed woodpecker along the Tensas River with a shotgun and took the specimen to his state wildlife office in Baton Rouge. By 1944 the last known individual of the species, a female, was gone.

During the Reconstruction Period after the Civil War, vast swaths of the Southern Forests were mowed down. Today all that remains of The Big Woods is a small 500,000-acre sliver. And with this loss Ivory-Billed Woodpecker populations rapidly declined. Despite warnings a decade earlier, many Southerners fought the news. In 1932 a Louisiana state representative, Mason Spencer, disproving of the reports heralding the demise of the species killed an ivory-billed woodpecker along the Tensas River with a shotgun and took the specimen to his state wildlife office in Baton Rouge. By 1944 the last known individual of the species, a female, was gone.

Everything changed on February 11, 2004, when at 1:30 P.M. Gene Sparling, a naturalists, was kayaking through the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge in Arkansas. A huge woodpecker with a red crest flew toward and landed on a nearby tree. Sparling stated the markings were very consistent with an Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. Cornell ornithologists, after talking with Sparling, mounted an expedition to Arkansas with Sparling as their guide. That team spotted this rare species but gained no documentation of it. “As he finished his notes, Harrison sat down on a log, put his face in his hands, and began to sob. ‘I saw an ivory-bill,’ he said. I stood quietly a few feet away, too choked with emotion to speak,” Gallagher said.

Everything changed on February 11, 2004, when at 1:30 P.M. Gene Sparling, a naturalists, was kayaking through the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge in Arkansas. A huge woodpecker with a red crest flew toward and landed on a nearby tree. Sparling stated the markings were very consistent with an Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. Cornell ornithologists, after talking with Sparling, mounted an expedition to Arkansas with Sparling as their guide. That team spotted this rare species but gained no documentation of it. “As he finished his notes, Harrison sat down on a log, put his face in his hands, and began to sob. ‘I saw an ivory-bill,’ he said. I stood quietly a few feet away, too choked with emotion to speak,” Gallagher said.

In 2005, the Cornell team published their results in the prestigious journal Science.

“Visual encounters during 2004 and 2005, and analysis of a video clip from April 2004, confirm the existence of at least one male. Acoustic signatures consistent with Campephilus display drums also have been heard from the region.”

Indeed, between February 11, 2004, and February 14, 2005, the search team lead by John Fitzpatrick reported at least 15 sightings of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Seven of these included sufficient details to include in the Science article. Besides the visual evidence, there are recorded Ivory-bill Woodpecker songs from 2005 as well. The sounds of the Lord God Bird is distinctive, a hant that sounds like a toy trumpet repeated in a series as well as quick double knock drumming (NPR has both early 1900 confirmed Ivory-bill songs as well as the recordings from 2005). However, Auriel Fournier, a Ph.D. candidate at University of Arkansas who works with wetland rails in the state, states that these comparisons can be difficult because the historic audio recordings are often of poor quality and difficult to compare to modern recordings.

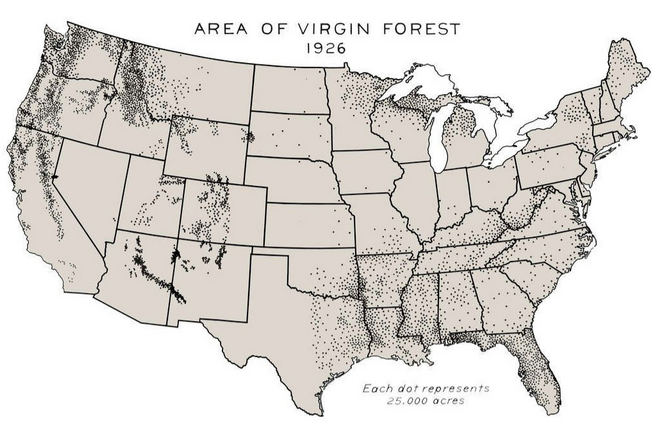

Yet despite this purported evidence, many scientists and professional birding organizations do not agree. The video of the single Ivory-billed woodpecker has been analyzed by almost every ornithologist, birder, and avian organization in existence. Less than year later, a team led by David Sibley (you likely have one of Sibley’s bird books on you shelf) published a reply in Science.

Yet despite this purported evidence, many scientists and professional birding organizations do not agree. The video of the single Ivory-billed woodpecker has been analyzed by almost every ornithologist, birder, and avian organization in existence. Less than year later, a team led by David Sibley (you likely have one of Sibley’s bird books on you shelf) published a reply in Science.

“We reanalyzed video presented as confirmation that an ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) persists in Arkansas. None of the features described as diagnostic of the ivory-billed woodpecker eliminate a normal pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus). Although we support efforts to find and protect ivory-billed woodpeckers, the video evidence does not demonstrate that the species persists in the United States.”

The Fitzpatrick team responded that the evidence clearly contradicted the claims of Sibley’s team. Further criticism of the Cornell team’s work also occurred in the leading ornithology journal The Auk.

“Prum, Robbins, Brett Benz, and I remain steadfast in our belief that the bird in the Luneau video is a normal Pileated Woodpecker. Others have independently come to the same conclusion, and publication of independent analyses may be forthcoming […] For scientists to label sight reports and questionable photographs as ‘proof’ of such an extraordinary record is delving into ‘faith-based’ ornithology and doing a disservice to science.”

Outside of this, Jerome Jackson included eight reasons why the bird could not occur in Arkansas. This criticism, not unexpectedly, elicited a response from the Cornell team.

“An invited article recently published in The Auk (Jackson 2006) presented a series of factual errors and poorly substantiated opinions about our work (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005) and our continuing research on the status of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) in eastern Arkansas. Despite being neither peer-reviewed nor fact-checked by the Editor, that article was treated as a scientific contribution by the public media, a perception actively fostered by its author in public appearances and interviews. Here, we correct and clarify the published record regarding the Ivory-billed Woodpecker rediscovery, our actions and motivations, and the conservation efforts now underway.”

Overall, it appears the birding community still disputes that Lord God Bird still exists.

“The vote on the Luneau video was unanimous not to accept the identification of the bird as an Ivorybilled Woodpecker. Dunn commented that with many rare birds now being photographed, and with the images posted to the internet often within hours, it seems inconceivable that populations of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in the eastern U.S. could completely evade the efforts of birders and photographers to document their existence…The American Birding Association Checklist Committee has not changed the status of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker from Code 6 (EXTINCT) to another level that would reflect a small surviving population. The Committee is waiting for unequivocal proof that the species still exists.”

All this raises a serious question, if we do find a Ivory-billed Woodpecker, what do we do with it? Fournier explained that the purported sighting had kicked off a debate in the birding community. The “unequivocal proof” that the species exist requires at the minimum a DNA sample to compare to the dozens of sequences already on file. Yet, nothing short of DNA and a specimen in hand to eventually be deposited into a museum is likely to drive consensus on the Ivory-bill’ existence. If a breeding pair or pairs could be located could we remove them from wild and being a captive breeding program, similar to that of the California Condor? Conversely, this proof and gambles on the species longevity require the reverse gamble and impact of removing the last individuals or even the very last Ivory-bill from the wild.

Why does so much mystique and attention center on the Ivory-billed Woodpecker? Two other species of birds in Arkansas are endangered, the red-cockaded woodpecker and the interior population of the typically coastal Least Tern. The Carolina Parakeet, the only native parakeet to North American, has been thought extinct since 1920’s. Despite this the money flying around and expeditions launched to rediscover the Carolina Parakeet. Fournier explains some of the attention of Ivory bill is because of its brilliant red plumage and its ginormous size but more importantly the idea of a bird coming back from extinction is a powerful narrative. “Of course the idea of a Ivory-billed Woodpecker hanging out in the remote swamps of Arkansas also doesn’t hurt with the mystery.”

Even if the Ivory-bill Woodpecker does still exists, the bird it likely not very abundant, less than a few breeding pairs. When I suggest than a couple of dozen pairs would be likely all we would find at the best, Fournier responds that “If we find a couple dozen that would be truly exciting, just not very likely.” Rather a few or dozens, it is hardly enough to keep the species going.